Grand Chief Littlechild: the “Long Road” to the Papal Apology and the United Nations Declaration

By Nancy J. Coombs, Founder, HCT Indigenous Issues Series

spoke in the HCT Indigenous Issues Series on April 8.

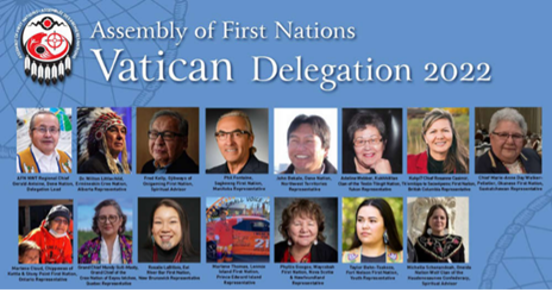

Summary: Having met with Pope Francis as part of the delegation of First Nations survivors and leadership, Grand Chief Wilton Littlechild shared his insights from that crucial conversation, the Papal apology and trip to Canada. He also talked about The United Nations Declaration’s history, implementation in Canada and importance in affirming rights and renewing relationships. He touched upon The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the repudiation of the “doctrine of discovery” and terra nullius. A global audience included Harvard alumni, guests, teachers and their students watching this important live event.

The HCT series was launched last year on Canada’s first National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, highlighting active allyship. Chief Littlechild personifies the spirit of this series. Not only he is a leader, he is the catalyst for lasting change and hope. Chief Littlechild’s recent accomplishments in Rome cap a lifetime of work and dedication. Other Indigenous leaders note his integrity: “Who he is, his personal history and how he presents himself – these are the things that make him a catalyst.” Chief Littlechild is a global leader for Indigenous rights, and his internationalism is deeply rooted in his community, his land, his local identity.

Chief Littlechild is a lawyer, born in Hobbema, Alberta, who has served as Grand Chief of Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations and elected Member of Parliament. A residential school survivor, he was the first status Indian from Alberta to obtain a law degree. In 1976 the Cree Nations bestowed him with a headdress as honorary chief and his grandfather's Cree name which means Walking Wolf. A member of the 1977 Indigenous delegation to the United Nations, he has worked since then on the UN Declaration. Chief Littlechild was commissioner to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada from 2009-2015. Today he is a practicing lawyer on the Erminiskin Reserve in Alberta. He also is a highly accomplished athlete and inductee into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame. Creator of the North American Indigenous Games, he has been awarded the Order of Canada, the Canada 125 Medal, the Pearson Peace Medal and many honorary doctorates.

Chief Littlechild spoke to the HCT from the Erminiskin Reserve, beginning his greetings in Cree. He was pleased that the event started with a land acknowledgement as a sign of solidarity. Elders took him into ceremony many years ago, before he began this work, and expressed their concerns to him about the violation of sacred agreements with the Crown through Queen Victoria dating back to 1876. They expressed three priorities: recognition, respect and justice. “That’s all we want,” they said. From that time, he has felt a duty to honour their trust in him.

He described how Indigenous peoples were not considered human beings under the Universal Declaration on Human Rights adopted in 1948. One of the elders had an innate understanding of the implications of the way forward, saying, “If they recognize us as human beings, they are going to have to admit we have human rights.” Chief Littlechild told the group that an eight-year battle ensued “to convince the United Nations we were human beings.”

Since violation of treaties was a main concern for the elders, he needed to convey their “oral testimony, their Indigenous understanding of our treaty.” Dispossession of lands and racial discrimination against Indigenous peoples needed to be addressed. He explained that they “had to borrow speaking time from NGOs who had authority to speak at the UN” since Indigenous peoples did not have a voice. In 1984 a working group was established at the UN on “Indigenous populations” with a two-fold mandate: review recent developments globally on Indigenous peoples and develop standards. “That was when they decided to make a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples.” But it was a slow process. Finally, the leadership allowed them to speak on this matter, “opening the door to participate in time-limited, two to three-minute interventions.”

He also shared that Canada had voted against the Declaration earlier since “genocide was mentioned and it didn’t want the Indian Residential Schools history to come to public light.” He called that school legacy “the darkest, saddest chapter in Canadian history.” Other countries that voted no, at that time, were the United States, Australia and New Zealand.

After decades of limited opportunities, things opened up in a big way, he said, when Canada took the floor at the UN recently to declare its support and endorsement without qualification of the United Nations’ Declaration. Chief Littlechild emphasized that it does not create new rights but has four main pillars: self-determination; free, prior and informed consent; lands, territories, and resources; and culture. He outlined its 46 articles, including preamble, and said, “You will see it is not lengthy but it took 27 years of debate.” Why so long? “One of the main reasons, in my view, is we wanted to share the same human rights from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted in 1948.” Being recognized as human beings would grant a right to self-determination and other rights.

Bill C-15, Canada’s UNDRIP Act, assures that the national laws and policies are in compliance with the United Nations Declaration. Chief Littlechild called it a “very significant step forward in our relationship.” He called UNDRIP a “blueprint for advancing reconciliation.” He spoke about the 7000 stories of abuse of children revealed in the Truth and Reconciliation of Canada, of which he served as Commissioner. He took that history with him when he met with Pope Francis, earlier that week. Meeting the Pope “I looked in his eyes and said I wanted to hear three words” and that he wanted him to come to Canada to say it directly to survivors. The Pope said “I’m very sorry, going beyond the calls to action, and also committed to come to Canada to visit with Indigenous survivors and Canada as a whole.”

He said that it was part of a journey, calling it “a start, a turning point.” He said, “It was a great honour for me to ask His Holiness the Pope to ensure, support, and endorse the principles of reconciliation which are now adopted by the UN as international principles for reconciliation.” He called it “successful” and with a reflective pause, added “It was a long way to Rome.” Now “the work begins on reconciliation. How do we restore respectful relationships? How do we now work together? For example, on treaties as a strengthened partnership.”

Professor Dan Berbecel, of Glendon College, moderated the Question and Answer segment, including one about whether decolonization was synonymous with reconciliation.

Chief Littlechild expressed regret that Pope Francis did not repudiate outright the Papal bulls relating to the doctrine of discovery and terra nullius. “He did not address those but did address the impact of colonialism on people through the links to Residential Schools.” The Pope “opened the door by introducing colonialism and its impacts on us which will lead to a discussion on the doctrine of discovery and terra nullius.”

Chief Littlechild stressed the importance of an apology, when harm’s done. Many people have not had the chance to experience the next important element “which is to forgive.”

“Many people are still angry, upset, and refuse to accept the apology – it is because they did not have the chance to forgive. I say to them, ‘Reconciliation begins with me, individually.’ Then when you have the opportunity to forgive, you have a sense of healing. When that happens, justice, the third dream of my elders, begins to happen. At that point, you can begin to have a true dialogue on reconciliation. It’s a long process – we never said it was going to happen overnight. But the truth, the apology, forgiveness, healing, and justice must all occur – then it can go to reconciliation.”

He said important next steps include Canada’s action plan to implement the UNDRIP Act and the establishment of a National Council for Reconciliation, an independent mechanism to monitor activities, issue a report to parliament and call on the Prime Minister.

He stressed, in closing, the “tremendous amount of goodwill and effort to advance reconciliation happening across the country.”

Ethel Billie Branch – former Attorney General and current candidate for President of Navajo Nation in addition to being an HAA Board Member – said in the chat, “Thank you Chief Littlechild for sharing your profound experience in fighting for the recognition of our people as equal human beings and equal sovereigns in the world community.” Attendee Leonida Rasenas expressed that “although your work has been on matters of Indigenous peoples, you are a positive force for all people and for the world.”

In closing, the HCT thanked Chief Littlechild for his powerful words, announcing a small contribution in his name to Indspire. Chief Littlechild was an Indspire Award recipient for Law and Justice. Indspire is an Indigenous national charity that invests in the education of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people, serving remote communities, rural areas and urban centres across Canada. Cliff Fregin, COO of Indspire who completed an Indigenous management program at Harvard Business School, was in attendance.

Through frank dialogues and active allyship, we work together for justice and reconciliation. Chief Littlechild has set an example on how to strive for goodness and healing while taking remedial action.

Here are some resources to learn about the United Nations Declaration, its implementation in Canada, as well as links to Indspire and HUNAP: